There has been no drought of media attention about coal, coal miners, and Appalachia over the past decade. I myself have fielded more than a dozen calls from media outlets who find this blog and want to know more about the region, each looking for new angles or “ins” with coal mines and coal miners. Though a few have done a decent job contextualizing Appalachia’s deeper issues, many still manage to skip over some very important details about our situation. Perhaps most important is that the systems of manipulation and exploitation that once ruled Appalachia’s coal company towns are still present in the region today.

The New Company Town

Those who have taken time to understand the history of Appalachia are familiar with the days of the coal camps and company towns. Northern investors purchased or otherwise extorted mineral rights and lands from Appalachian residents in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They then invested in building entire towns, including worker housing, general stores, churches, doctors offices, and even law enforcement and mercenary forces—all owned by the coal company. Companies then paid their workers solely in company scrip, a form of money that could only be tendered for goods and services at company owned establishments.

Many people likened working in coal camps to serfdom. For poor immigrants recruited at ports of entry in the Northeast, their work in the coal mines resembled indentured servitude. Once they arrived at the coal camp, they found they were required to pay the company for their family’s train ride, their first month’s rent, and all tools necessary to mine the company’s coal. In other areas, convict leasing laws within the Jim Crow south provided coal companies with cheap convict labor, such as was the case in Coal Creek, Tennessee and Birmingham, Alabama.

These were terrible times and mining families actively fought and died to escape the living conditions and control imposed on them by the coal companies. The Coal Creek, Cabin Creek, and Harlan County Wars, as well as the Matewan Massacre and the Battle of Blair Mountain, are grim reminders of those struggles. Better times didn’t reach Appalachia until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 which eliminated company scrip and helped establish a stronger union. With more and more miners unionizing, people living in and around mining communities were slowly beginning to enjoy basic human rights.

It is important to once again point out that many of the improvements that occurred for Appalachia’s coal miners did not come through newfound benevolent attitudes toward employees by company owners and investors. Mine safety legislation has always been reactionary to public outcry in the wake of terrible mine disasters. Concessions for better pay and benefits always came as a result of intense labor struggles that included countless strikes by union miners. Even mechanization and other improvements in mining technology played a role in improving mining conditions. But to think that the coal industry simply gave up their desire for cheap, expendable labor, is, for the lack of a better term—f***ing ridiculous.

While coal companies did profit from the sales in their stores and from the rent paid by families for housing, it was their ability to keep mining families in a form of desperate captivity that profited them the most. Doing so meant keeping them in a perpetual state of debt for the things their families needed. They simply handed this task over to local chambers of commerce.

In local mining communities, having a paycheck from a coal company is instant credit. Automotive dealerships, local banks, and mortgage companies all readily offer lines of credit to coal miners. Even during the massive layoffs that came in 2013, one auto dealership advertised that if a miner lost their job within two years of buying a new truck, they would simply take it back without any damage to their credit. Mortgage companies were less forgiving.

For years Farmers and Miner’s bank advertised loans on billboards with images of motorcycles, boats, homes, and vacations, directly targeting miners. In 2013 when the layoffs came, many billboards were replaced with images of casually dressed bankers shaking the hands of farmers with statements professing that themselves as being “Your friend in the community.”

With mining jobs on the decline, the real estate market also plummeted, trapping many families in the region who are unable to sell their homes. Others foreclosed, handing over yet more land and mineral rights to outside companies while they themselves were cast into poverty.

Mono-Economics

By ensuring no job alternatives exist offering a living wage, families with generational ties to their land, or those who are financially incapable of moving away, must do what they must to survive. This was what led myself, my father, and my grandfather to work in the mines. When moving away wasn’t an option financially, we wanted to remain close to home, to raise our children in the same valley that our ancestors settled nearly two hundred years ago. Without enough land to farm, and few if any good paying jobs outside of the mining industry, we had little choice for a profession.

If there were jobs that offered similar wages without the dangers and long-term health issues of mining underground, we would have all jumped at the chance. Indeed, many of the miners I worked with came to the mines as a last choice after having tried to survive otherwise. We all learned that the coal industry maintains a monopoly on living wage jobs in the region. What few well-paying jobs do exist, such as working for railroads or local utilities, remain highly competed for beneath systems of nepotism.

Half of the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority’s board of directors were high-ranking officials in the local coal industry during the last coal boom (2005 to roughly 2013). Some may argue that this agency, and other government agencies aren’t fully to blame for the lack of economic development, citing the infrastructural problems created by our mountainous topography. But our topography isn’t much different than say, the Poconos, the Catskills, the Blue Ridge, or the Alleghenies.

The problem with economic development in central Appalachia lies within the extreme wealth of coal that exists here and the systems of power created and maintained by all of those who benefit from its extraction and sale. It is the natural resource curse housed within our own country.

Education

Education, or more importantly, the lack thereof, is yet another means of maintaining a captive workforce in coal mining regions. The theory of trickle-down economics, combined with the absentee (outside) land ownership of our region, means that local property taxes are kept low for the corporate interests. This places the tax burden on local citizens who are already struggling through poverty. The result is limited revenue for public services, including public education where school systems fight to maintain facilities and teacher salaries.

Local schools are shut down and consolidated, class sizes are increased, and teacher’s wages and benefits continue to suffer. Students who attend schools in Appalachia’s coalfields have severely reduced chances of gaining the social mobility necessary to escape poverty in the region, much in the same way minority communities face the same issue, just without the school-to-prison pipeline faced by African American youth.

High school students graduating in the region are woefully unprepared to compete in the outside workforce, let alone gain acceptance to many colleges and universities flooded with applications from more privileged parts of the nation. When a coal company offers $60,000 to $80,000 a year to a high school graduate, and banks advertise loans for nice new homes, pickup trucks, and boats, students are faced with a terrible choice, take a chance at the short-lived Appalachian Dream, or face abject poverty dulled by substance abuse.

It’s a win-win for the companies and the banks: tax breaks, a captive workforce of people the rest of the nation as “dumb hillbillies,” and more land and mineral rights to foreclose on when the coal markets plummet.

If these economic drivers were not enough to fully implement their design to maintain a captive workforce, coal industry associations, through organizations like Coal Education Development and Resources of Southern West Virginia (CEDARS), work to manipulate the local cultural history of the region by teaching kids in public schools by re-writing the local history and teaching about the benefits of coal. For instance, they state that “Today many decry conditions in the ‘coal camps,’ but miners and their families fared as well as most working-class Americans, and better than those unfortunate souls who labored in urban sweatshops or as rural sharecroppers.” They also re-contextualize the labor struggles as a power struggle between labor unions and companies for the “control of the coal industry.”

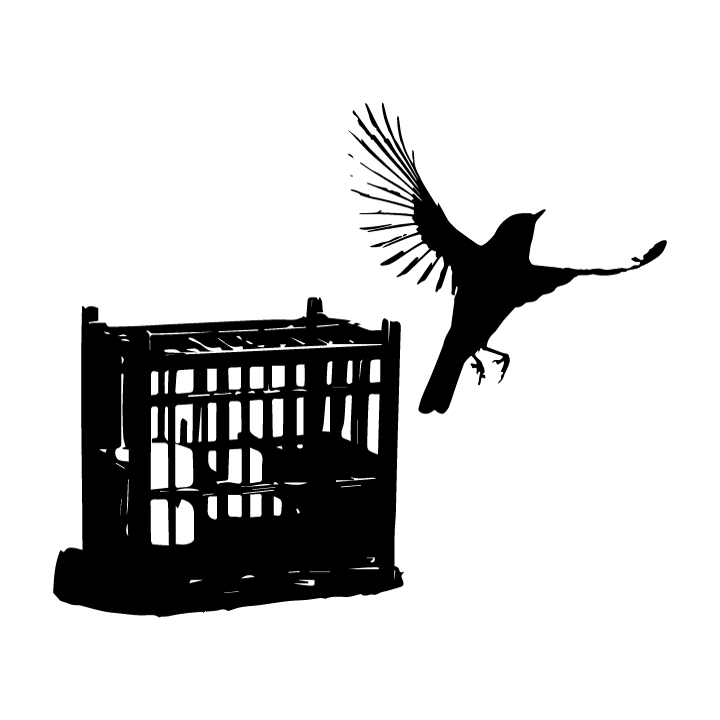

While federal regulations may never allow coal corporations to return to the days of company towns, they still have Appalachians held in a perpetual state of economic captivity. They have their pick of miners desperate to support their families, desperate to have healthcare benefits, and desperate to save their homes (and family land) from foreclosure. They have families willing to do anything, willing to vote for anyone, to alleviate their suffering—all while being told by company public relations that their suffering is the result of a “War on coal.”

More miners are working 10 to 12 hours a day for weeks on end, breathing more dust, earning less pay, and receiving fewer benefits. It all spells misery for coal mining families who are held as economic prisoners within their mountain homes.

Though people like J.D. Vance would have us pull up our bootstraps, go into the Marine Corp, and then go to university and then Yale Law School, this is not the reality Appalachian people face. We did not grow up in Middletown, Ohio. We grew up in the Appalachian coalfields.

These are the problems that I try to explain to journalists and those who choose to look down upon us. I’ve written and re-written about these issues. There is no lack of evidence or of common sense to deny it. These are the truths that need to be at the forefront of media reporting on the region.