COVID created a lot of anxiety throughout the nation. It also started a mass out migration from the nation’s urban centers that’s leading to the gentrification of low-income rural communities. Hyper-inflated housing markets, rising costs of living, and loss of local culture are just some of the problems compounding already difficult situations.

In rural communities throughout the nation, housing costs have literally doubled. Speaking with real estate agents, I have been told that properties are being bought “sight unseen.” In other words, urban dwellers with disposable income are cruising the internet, finding properties, and buying them without even looking at them in person. “They have the money,” one realtor told me over the phone, “They can.”

A loan officer/realtor at a local credit union reaffirmed the problem, telling me the story of a friend who wanted to put their house on the market. “I warned him multiple times that he needed another place to live before putting his on the market,” she explained. “It hasn’t been uncommon to sell a home in less than 24 hours. He didn’t listen. When he had me list his house and property for him, it went under contract in just four hours.”

People from out-of-state weren’t just buying one home and creating bidding wars on them either, they were buying multiple properties and turning the others into rentals and Air BnBs to generate passive income off of local families. The loan officer went on to say, “They can sell their higher-value properties in the cities with equity that allows them to come out here and buy up what it takes local folks a lifetime to afford. A lot of these buyers are working remotely too, so they can keep their high paying city jobs.”

She wasn’t wrong. After a desperate search for housing to take a new teaching job, we ended up renting from a Long Island couple. The woman still worked for hospitals in New York despite being more than six hours away. They were also charging us cost-burdened rent at $1,800 a month to help cover their new mortgage in an area as impoverished as the coalfields. It was a win-win for them, but not their new community.

Gentrification in a Nutshell

What we are witnessing is gentrification, which, until now, was largely reserved for cities. According to Merriam-Webster:

gentrification jen-trə-fə-ˈkā-shən noun: a process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild homes and businesses and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents

It’s a conversation that comes up a lot with my brother who now lives in rural East Tennessee. The past four years have brought lots of property purchases by people with license plates from California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois.

“Someone actually bought that property there,” he pointed out as we were driving by. It was a small, forested knoll of a hill that was straight up and down. “Another sight-unseen purchase. You can barely get a bulldozer up the damn thing.” I could see where they’d attempted to clear off a place. It wasn’t happening. “Dumbasses,” my brother said. “In just two years the tax appraisal for my property has doubled—literally doubled—because of all this.”

When tax assessments go up, people feel it. I’d spoken with a rural town manager who told me of his town’s predicament. “We are about to lose state funding. We have tried to keep property taxes low knowing how it would impact the majority of our citizens, especially after all the manufacturing left.” He shook his head, “But with the crazy increases in real estate prices [what the state bases some of their funding on], we are being told we have to raise property taxes and start paying for things ourselves. Just because people’s property values go up doesn’t mean they also get better jobs with substantial pay increases.”

Not only are rural housing markets through the roof, most communities do not have the local economy and jobs to support inflated property values and rising costs-of-living. And the costs-of-living do rise, quickly.

It reminds me of something my mother told back in the 80s when most coal mines were still union. “Every time the union signed a new contract with a pay raise for miners,” she said, “local grocery store prices go up across the board.” Just more proof that the company town mentality of exploiting workers never left, it was just expanded to allow outside business owners to do the same.

What has been crazy to me is that the coalfields are starting to see it as well. There are more luxury vehicles and people walking through the local grocery stores with high-end clothing. When I noticed a women in a local coffee shop dressed to the nines, the owner noticed me noticing them. After she was done with her purchase and I stepped to the counter and the owner told me, “She’s from California. Bought a $250,000 farm in Russell county sight unseen. She told me she bought an even bigger farm for her son somewhere in West Virginia.”

Ignorance is Bliss

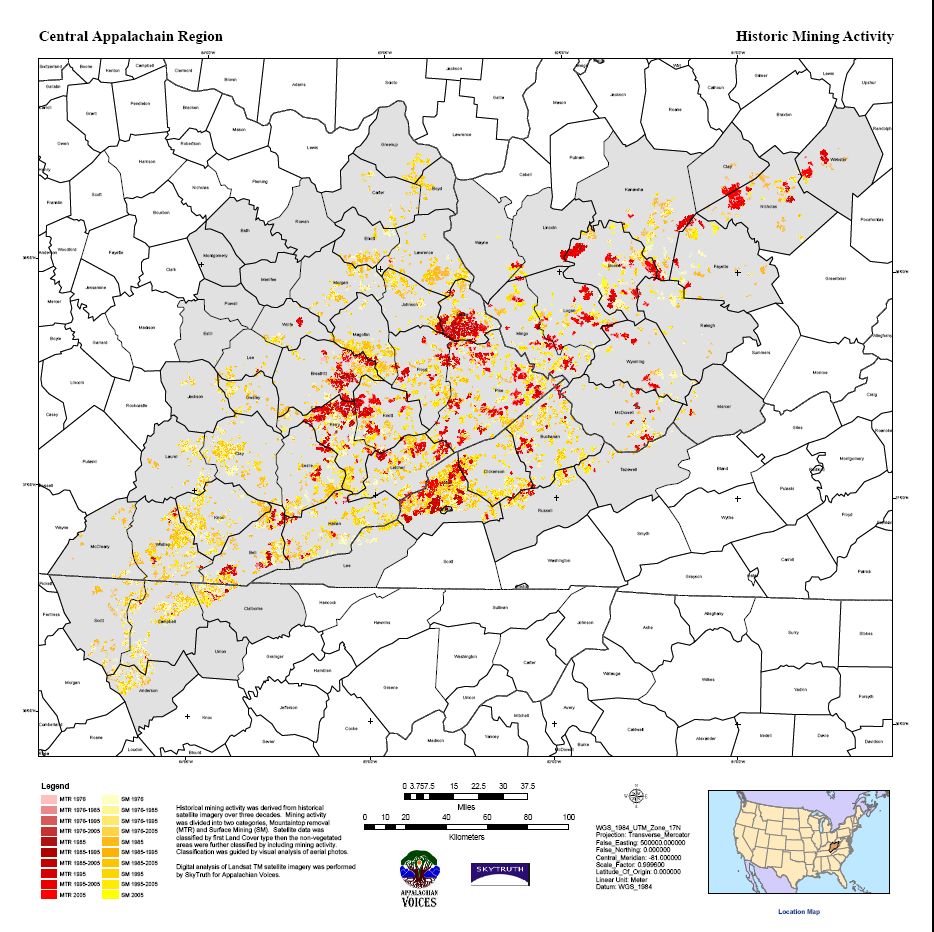

As a former coal miner turned environmental activist, I have a pretty in-depth knowledge (pun fully intended), about the legacy of environmental health impacts facing our region.

A trip into the coalfields usually doesn’t scream “get the hell out of here!” There are no signs with skulls and crossbones, no warnings to keep out, and not even that many mines to look at. In fact, thanks to the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, most mine sites have been reclaimed to their original contour and are now covered with autumn olives and other invasive species.

Coal operators have also been smart to put extra effort into mine reclamation areas visible from local highways. From safety violations to disasters, the mining industry has always done an excellent job covering things up when they need to. What did they say the Buffalo Creek Disaster was? An Act of God?

It is the legacy of coal mining pollution that we need to be worried about. Mining contamination of surface waterways and underground aquifers will plague future generations for centuries to come no matter how much things look better on the surface.

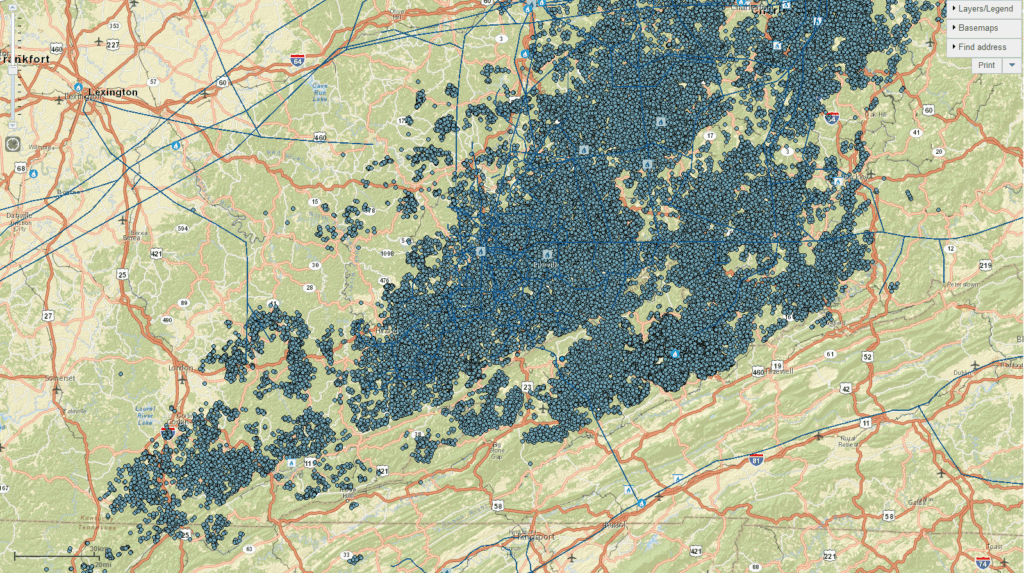

And don’t get me started on the natural gas wells and the hydraulic fracturing Haliburton perfected in these areas during the 1990s.

The poor and working poor do not have the time or energy to care. Coal miners ignore it to keep their jobs. Yes. I will quote Upton Sinclair again, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” So what will be the attitudes of the newest coalfield citizens?

Something tells me that not many know about what’s going on around here environmentally. I’m guessing they’d probably be interested in seeing how the first Trump administration halted a study by the National Foundation for the Sciences investigating the higher rates of cancer, kidney diseases, and birth defects in coal mining communities.

Sadly, these new folks aren’t alone in their ignorance of these issues. Younger Appalachians whose families have lived here for generations are equally ignorant about the legacy of health impacts from coal mining. Many have never been taught about their local history, including the violent labor struggles for basic human rights and myriad of preventable coal mining accidents and disasters. I was surprised when kids in local schools struggled to even know where coal came from and why burning it was such a big deal.

Fewer still knew about the problems of surface subsidence, coal slurry impoundments, acid mine drainage, and total dissolved solids in the water. With most mining shut down, it’s largely out-of-sight out-of-mind, even for local folks.

Maybe Gentrification Isn’t All Bad?

Not everyone coming to the coalfields is independently wealthy. Some are working class folks who are moving here to reduce their debts and property tax liabilities. While they do possess more money, it’s hard to count it as gentrification. That’s the case for the newest addition to our hollow, the first out-of-state individual to move in in perhaps more than 70 years. So far they are pretty good people, a lot like us, just from a different place.

I’ve also met transplants escaping intense poverty in Connecticut and New York to find a slower paced life with less crime. And then there’s GoodTimes Coal Fired Pizza and Pub that opened in Big Stone Gap, Virginia. In our first visit, I spoke with the bartender (and owner’s son-in-law) who shared some their story.

They were suffering from their own gentrification issues in Northern California, so his in-laws took a trip to Virginia to see about a new home. Big Stone Gap was one of their first stops, and turned out to be their only stop. They fell in love with the town instantly.

Granted, Big Stone Gap is easy to fall in love with. It’s the nicest place around which is why all the coal operators, doctors, and company lawyers have traditionally lived there. It’s also no coincidence their municipal water source comes from the nearby National Forest rather than the Powell River whose headwaters have been seriously impacted by mine pollution.

I was nevertheless happy to see they had decorated with coal mining memorabilia, including two frames containing old Westmoreland Coal Company stickers, and United Mine Workers T-Shirts from the Pittston Strike in 1989. “We wanted to honor the area’s coal history,” he said. I thanked him because, as I mentioned before, some of that history is being lost among newer generations.

Seeing and learning this, it became hard for me to dismiss some of the possibilities new folks could bring for our region. GoodTimes was a happening place, bringing locals together, and even showcasing a lot of their talent by hosting music performances and karaoke nights.

An influx of new people doesn’t have to be a bad thing, especially if newcomers are aware of how gentrification works and ways they can avoid harming the communities they move into.

Appalachia’s population is aging, and despite the vastly depleted coal seams and dwindling number of mines, the coal and natural gas industries still have tremendous control over the region’s economics and politics by owning a majority of the private land and mineral rights. What if new folks were better prepared to recognize the corruption and injustice? What if they took up the cause of land and tax reforms while holding coal companies accountable for environmental cleanup? That would be interesting.

If history has taught us anything in these mountains, it’s that change is a constant. As we contend with political and economic upheaval, and lets not forget weather extremes created by climate change, it will be important to keep a positive outlook and come together to work as communities…like we used to.

Gentrification can certainly cause many issues, but if those moving to the area take time to understand our situation, learn the history, and strive to avoid causing issues, it could be a blessing. Better yet, they could take up the cause of fighting injustice in our communities, giving us the help we’ve long needed to achieve a just and equitable transition.