As a coal miner, I worried more about sudden death rather than the long term debilitating health effects related to mining. Whenever the subject did come up, it centered upon Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis (CWP), also known as “black lung.” I eventually realized there was a much bigger picture however, and CWP was only the tip of the iceberg.

Underground mining not only fills a miner’s lungs with dust, it wears out the body and can even cause cancer.

With ever increasing production quotas, coal mining has become faster paced during recent years. The rigorous work required in confined spaces leads to joint deterioration, especially within the lower back, knees, shoulders and neck.

Newer generation miners suffer from such injuries despite only a few years of working in the mines. Those who are financially bound to their jobs rely upon pain medications to continue working. As a result, prescription medication abuse within the coal industry has steadily risen over the past decade, a problem that has even spread throughout the surrounding communities.

“I can’t get on disability,” one young miner, wishing to keep his anonymity explained. “There is no way I can afford my house payments and support my family on social security checks. I have to do what is necessary to keep going an’ keep working.”

Miners must also face constant exposure to various chemicals in the mines. Ted Mullins, a retired electrician who worked in an underground coal mine/prep plant complex in eastern Kentucky, is now fighting an ongoing battle with leukemia.

“I sometimes wonder if a lot of the cancer me and many of my friends have been diagnosed with came from chemicals we were exposed to in and around the mines,” Mullins, who now lives in Lexington, Ky., said. He listed off several names of co-workers he knew–all of whom have have since died from cancer.

“Miners today don’t think about their health years down the road,” he said. “I’m just glad I retired union and have [United Mine Worker’s Association] retirement medical coverage. If I didn’t, there is no way I could afford to fight my leukemia.”

To make matters worse, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has lately examined the increased usage of diesel equipment in underground mining and the effects of exhaust on miners in confined spaces. A website published by NIOSH reveals potential links between diesel exhaust and cancer. According to the website, underground miners may be exposed to 100 times the amount of diesel exhaust as compared to the rest of the population.

While the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration and state mining agencies have put various laws regarding diesel equipment in place, miners are left to wonder if it will be enough. “NIOSH cannot definitely determine that current diesel regulations will result in the elimination of all diesel health concerns,” stated Ed Blosser, Public Affairs Officer for NIOSH. “The reason for this uncertainty is that there is still incomplete information concerning the level of exposure to diesel emissions that may cause health effects.”

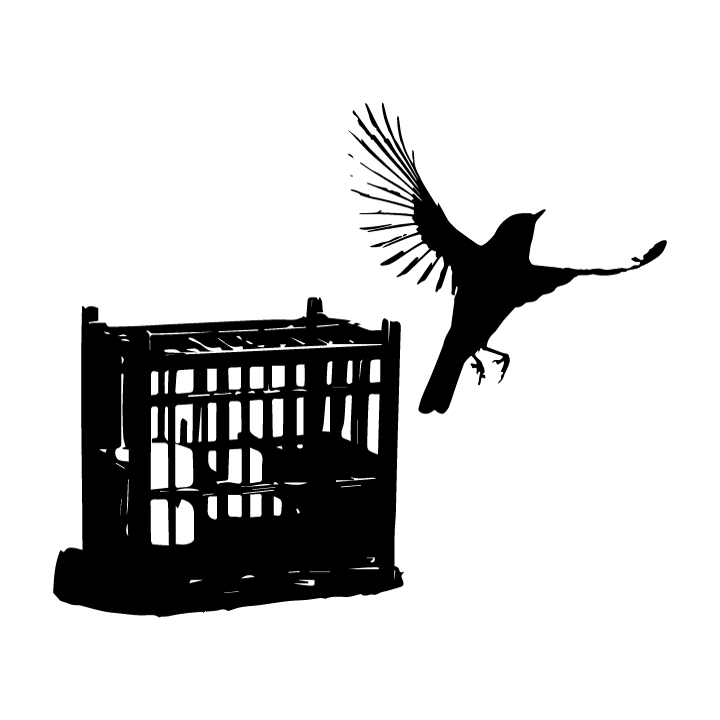

Anyone living within the coalfields will tell you that a coal miner who spends their life working in mines will be left with little health to enjoy retirement. A lot of miners make every effort to warn their children about following their footsteps into the mines, hoping the next generation will strive for a better education and avoid a similar fate.

As life would have it, many of those children become enticed by the high wages of coal mining as compared to other jobs in the coalfields. They look only at the short-term gains while ignoring the long-term losses.

As one of those young miners so eloquently put it, “You’ve got to die someday.”