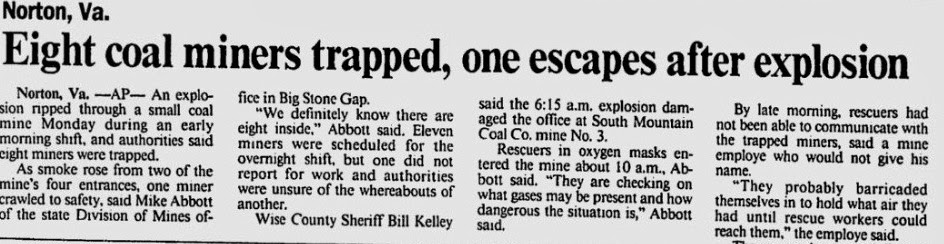

December 7th, 1992 was a cold Monday morning. My brother and I were getting ready for school when the phone rang a little after 6:45 am. Mom answered and immediately went into the bedroom to wake my father. There had been an explosion at the South Mountain No. 3 mine and there was no communication with the men inside. The No. 3 mine was just down the road from where dad worked and was owned by the same company. He knew several of the men who worked there, some of whom were friends of the family.

Dad immediately drove to Guest River to see if there was anything he could do to help. When he returned, his face was grim. He said there was thick smoke billowing from the mine portals, that the heavy conveyor belts from inside the mine were blown out and hung over the power lines, and that a drink machine on the outside had been blown entirely across the hollow from the force.

By midday, television crews and reporters from all over the nation had converged on Guest River. Local news showed the scenes just as dad had described. Smoke was continuing to pour from the mine portals as drilling crews had begun boring down to breech the working section of the mine, a standard practice for taking air samples and looking for signs of life. Despite the bleak situation, we all held hope that the men were still alive and that mine rescue teams could reach them in time.

As rescue efforts continued, mine owner Ridley Elkins saw fit to keep his other mine, Plowboy #4, running just up the road. Dad still had to report to work for the evening shift, even though the coal seam they were mining was situated directly over top South Mountain No. 3. He knew that the holes being drilled were likely going to punch through the sealed sections of his own mine as they attempted to get down to the other.

Dad and a few other miners protested keeping Plowboy #4 running while the rescue efforts were still underway. Not only did they understand the danger to themselves and their fellow workers, they had difficulty working knowing some of their friends could still be alive and trapped from the explosion. To this day my dad still recalls passing by the South Mountain mine lit up at night with emergency personnel and news crews swarming the area. “It was the hardest thing I think I ever had to do,” he once told me solemnly. “Go to work knowing them boys was still trapped in that mine.”

Two and half days later mine rescue teams reached the section. All eight men had perished.

David K. Carlton

Danny R. Gentry

James E. “Garr” Mullins

Mike D. Mullins

Brian Owens

Claude L. Sturgill

Palmer E. Sturgill

Norman D. Vanover

Elkins never shut down Plowboy #4—not even to give his other employees time to attend the funerals. He begrudgingly gave my father and two other miners time off, telling them coldly, “Just go home until them boys is buried.” Dad had to control himself to keep from punching Ridley in the face.

The day after the funerals, dad and several other quit. He later told me that he and the others called the federal mine inspectors and reported their concerns.

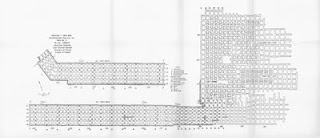

The following investigation revealed many problems at the South Mountain No. 3 mine. According the state report, the explosion was caused by:

- Improperly conducted weekly examinations for the No. 3 Mine and the 001 section on November 21-30, 1992. The certified examiner failed to examine the bleeder system in its entirety due to adverse roof conditions.

- An inadequately conducted smoking search program. Smoking material was found with three of the victims, and a lunch container was found to contain two full packs of cigarettes and two cigarette lighters.

- Failure to conduct a thorough preshift examination on the 001 section between 9:30 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. on December 6, 1992, for the oncoming midnight shift on the 1 Left 001 section.

- Improperly placed and maintained ventilation control devices.

- Failure to maintain the required incombustible content of the mine dust.

- Failure to follow the approved ventilation plan in the bleeder system inby No. 1 Left 001 section.

- Failure to provide the necessary volume and velocity of air in the 1 Left 001 section.

- Failure to conduct weekly examinations of the ventilation system at least every seven days.

But there was more to it than that.

The methane monitor on the continuous mining machine had been bypassed, allowing the machine to run (and continue producing coal) despite detecting explosive levels of methane gas. This, along with the failure of mine management (and some believe state and federal mine inspectors) to properly examine the mine ventilation systems—as mandated by law—led to ventilation problems thereby allowing methane to reach dangerously explosive levels. To save money on materials and labor, mine management had also failed to see that coal dust accumulations were kept in check and the appropriate amounts of rock dust were applied, an inert limestone powder meant to stifle coal dust’s ability to ignite when in the air.

Following the explosion, controversy arose around whether state and federal mine inspectors had done their jobs, especially with whether or not inspectors had physically gone into the mine to inspect mine ventilation, safety equipment, coal dust accumulation, and rock dust application as mandated by state and federal laws. It had often been rumored that inspectors would just sit out in the office trailer of the mine site, shooting the breeze with mine managers, and in some cases, even accepting “gifts” from small coal company operators.

For once, community members hoped that the defunct system of mine safety regulation would be seen for what it truly was, and maybe, just maybe, the system would be fixed. But during the investigation, officials supposedly “found” cigarette lighters and cigarettes in one of the fallen miner’s dinner buckets and on their person. The smoking materials instantly became the focus of the disaster’s cause, and an easily accepted scapegoat within the local media.

Family and friends of the fallen miners were outraged at the allegations.

People within the community, including other miners who worked at Elkins’ mining operations, suspected the cigarettes and lighters were planted during the investigation, put there to place blame on men who could not defend themselves. Many people still believe that this gave investigators a direct cause that would take attention away from the largest contributors to the explosion—the bypassed methane detector, the mine ventilation that was not kept in accordance with ventilation plans, the failure to keep coal dust under control by applying rock dust, and the failure of mine enforcement officials to properly inspect the mine for flagrant mine safety violations.

Afterwards, lawsuits were brought against some of the mine management, including Elkins who would only spend six months in jail for the deaths of eight men who their families would never see again. The company was also fined $2,000,000, of which only a mere $900,000 was earmarked to go to the families of the fallen miners. This was the extent of punishment for the loss of eight men’s lives, men who worked hard just to support their families. A little over $100,000 to support families who’d lost their loved ones.

Several years later, the widows of the fallen miners filed a lawsuit against the Mine Safety and Health Administration for not performing their duty. The story made the papers when a federal judge exonerated the MSHA officials, stating the accident was a result of the mine owner’s failure to maintain safe working conditions.

Today, a drive up Guest River reveals little more than years of mining by various operations. Only those most familiar could find the site where the mine existed. There are no markers, no memorials or wreaths, only continued feelings of injustice for the eight loved ones who perished deep beneath the mountain.