It’s difficult to discuss Appalachia without discussing our history. It comes up a lot in my posts, so rather than repeat myself, I decided to create this basic (very basic) Appalachian history page to help contextualize how Appalachia arrived at its current state. Think of this page as everything that J.D. Vance left out of Hillbilly Elegy when he generalized Appalachia through a few childhood trips and bootstrapping arguments.

First a couple of disclaimers. I am no historian, so I invite my readers to bring up any information I may have missed, additions, or corrections. This is also related to central Appalachia’s coalfields that include West Virginia, Eastern Kentucky, portions of Upper East Tennessee, and my home of Southwestern Virginia.

I also invite you to share any family stories you may have.

The First “Appalachians”

We were no the first people to live in these mountains. I feel like we often forget it given how our history is taught. “The winner writes the war,” as they say. Appalachia is, believe it or not, the Spanish name for these mountains. The name goes back to 1528, and the first European exploration of the region by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Núñez, and subsequent Spanish “explorers,” gave it the name based on a tribe of people he met in Florida before venturing north.1

But these mountains, creeks, rivers, and all of the trees, plants, and animals already had names given to them by the original inhabitants. The Cherokee named their home to the south of us “Sha-cona-ge,” or the “Land of the Blue Smoke.” I would have liked to known what this area was called in the various native languages, but we will likely never know. Such knowledge is now lost thanks to a genocide that began at the hands of British colonists and was ultimately finished by the new United States Government.

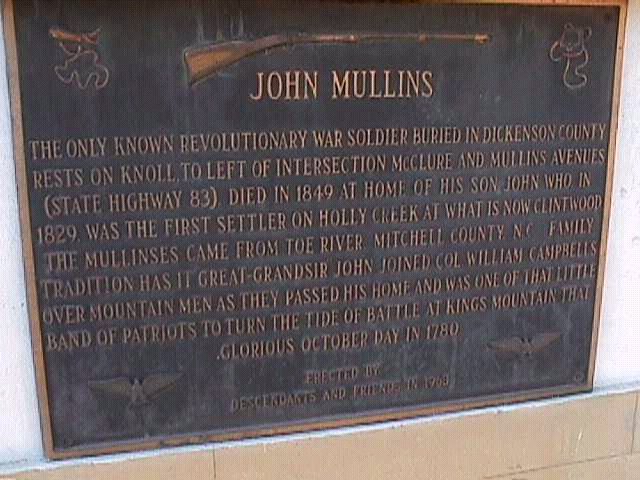

So far as we know, Central Appalachia was largely unoccupied by American Indian settlements at the time of colonization. The area was mostly hunted by long range hunters from various tribes including the Cherokee and Shawnee. Still, there are remnants of past settlements in these hills. Family members have told me of the pottery and arrowheads our early ancestors found beneath natural overhanging rock shelters throughout Dickenson county.

We should always remember that our Europeans ancestors were not the first to settles these lands. The American Indians were, in every right, the First Peoples. They existed within these mountains for thousands of years prior to our encroachment. They held a culture and understanding of life and balance that I personally believe was far superior to the egotistical, destructive greed of European whites. These lands were kept pristine until we got here.

Let us take a long moment to honor their existence and remember the horrific genocide enacted upon them by early British Colonists, and to a much more severe degree, the newly formed United States of America, both of whom used Scots-Irish ancestors to do their dirty work.

From Misery to Freedom

As for our migration into these hills, I will defer to an exerpt from Harry M. Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1963),

“And so for many decades there flowed from Merry England to the piney coasts of Georgia, Virginia and the Carolinas a raggle-taggle of humanity—penniless workmen fleeing from the ever-present threat of military conscription; honest men who could not pay their debts, pickpockets and thieves who were worth more to the Crown on a New World plantation than dangling from a rope, and children of all ages and both sexes, whose only offense was that they were orphans and without guardians capable of their care. Not all persons who came to the New World under such circumstances were brought legally, even by the loose standards prevailing at the time.

Not all children who found themselves in a ship’s hold outward bound for Charleston were orphans. Gangs of thieves prospered in the sordid business of stealing or “nabbing” children for the plantations. In the parlance of their day they were called ‘kidnabbers,’ a term later converted by Cockney English to ‘kidnapers.’ But the peril of kidnaping was not restricted to hapless boys and girls. Judging from an ancient song, adults, too, were shanghaied, and sometimes under truly agonizing circumstances:

‘The night I was a-married,

And on my marriage bed,

There come a fierce sea captain

And stood by my bed stead.

His men, they bound me tightly

With a rope so cruel and strong,

And carried me over the waters

To labor for seven years long.’

It is apparent that such human refuse, dumped on a strange shore in the keeping of a few hundred merciless planters [plantation owners]… Many of them died on the plantations under the whips of taskmasters. Some ran away and became pirates whose Jolly Rogers terrorized the oceans. A few, perhaps, rose over the heads and shoulders of their suffering fellows to become planters themselves. Others— and it is these with whom we are concerned— ran away to the interior, to the rolling Piedmont, and thence to the dark foothills on the fringes of the Blue Ridge. These latter were joined by more who came when their bonds [indentured servitude] had expired. And here we have the people— few in number, but steadily gaining recruits, living under cliffs or in rude cabins— who were the first to earn for themselves the title of ‘Southern mountaineers.’Slowly, in the last quarter of the seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth, these backwoodsmen increased in number. Steadily, newcomers pushed in from the coastal regions and the birth rate must have been, as it still is, prodigious. Thus by 1750 or 1775 there was thoroughly established in the fringes of the Southern Appalachian chain the seed stock of the ‘generations’ whose descendants have since spread throughout the entire mountain range, along every winding creek bed and up every hidden valley. The family names found in eastern Kentucky today are heard over the entire region of the Southern mountains. They bespeak a peasant and yeoman ancestry who, for the most part, came from England itself and from Scotland and Ireland.

By the time of the Harrodstown (now Harrodsburg) settlement, much of the pioneer society in this mountainous region had resided in the wilderness for three or four generations. They had already become thoroughly adapted to their environment. They had acquired much of the stoicism of the Indians and inurement to primitive outdoor living had made them almost as wild as the red man and physically nearly as tough.

The white backwoodsman had learned, perhaps from the Cherokees, how to build cabins, and had improved the structure by the addition of a crude chimney. His ‘old woman’ could endure hardships and privation as well as the Indian squaw, and was far more fruitful. Having never been exposed to the delights of civilization, she was willing to follow her husband wherever wanderlust and a passion for untrammeled freedom might take him. And the mountaineer needed few implements and skills to live by kingly standards (to him) anywhere in the Appalachians, or in the rolling meadowlands beyond.

He had learned to clear the narrow bottoms for the cultivation of Indian corn, squash, potatoes, beans and tobacco, and from the sale of skins and other forest products he had acquired an ax and the Pennsylvania ‘Dutch’ rifle and lead and powder. Salt could be obtained at natural licks, and all other things essential to his well-being could be acquired in the forest.”

Our people came from tremendous adversity before escaping into the mountains. They began living and understanding a new type of freedom as they adapted to the free land-based cultures of the American Indians. They came to love the mountains, and passed that love down with each generation. Sadly, it wouldn’t last long.

Following the Revolutionary War, westward expansion brought an influx of people to the region straining relations with many American Indian tribes. Tribes who resisted (and even those who did not) ultimately faced the atrocities of the Indian Removal Act. Throughout this turmoil early Appalachian settlers began to face new challenges as well.

As more people flooded to the region so did the many ills of society. Demands on natural resources grew as did the idea of land ownership. Three decades later the Civil War ripped through many of our communities, further politicizing the region, and creating resource scarcities that led to intense suffering (Eller, 1982; Straw & Blethen, 2004).

During reconstruction, northern interests discovered the abundance of coal and timber resources throughout our region. Beginning in the late 19th century businessmen, known as land agents, began buying timber and mineral rights from Appalachian subsistence farmers. Appalachia is full of family tales about these smooth talking land agents and their false promises. The often illiterate mountain farmers did not understand the documents they were signing,2 nor were they told the true value of coal and minerals they were selling. (Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force, 1983; Eller, 1982; Straw & Blethen, 2004)

In other locations, courthouses containing people’s land deeds mysteriously caught fire in the middle of the night. Afterward, farmers living in those jurisdictions had their land titles challenged by lawyers and surveyors hired by outside investors to obtain mineral rights (Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force, 1983). Having little money (which they often didn’t need) and being unable to hire their own lawyers and surveyors, poor farmers were ultimately coerced—under the threat of eviction—into giving up their mineral rights in exchange for maintaining surface ownership of their farms.

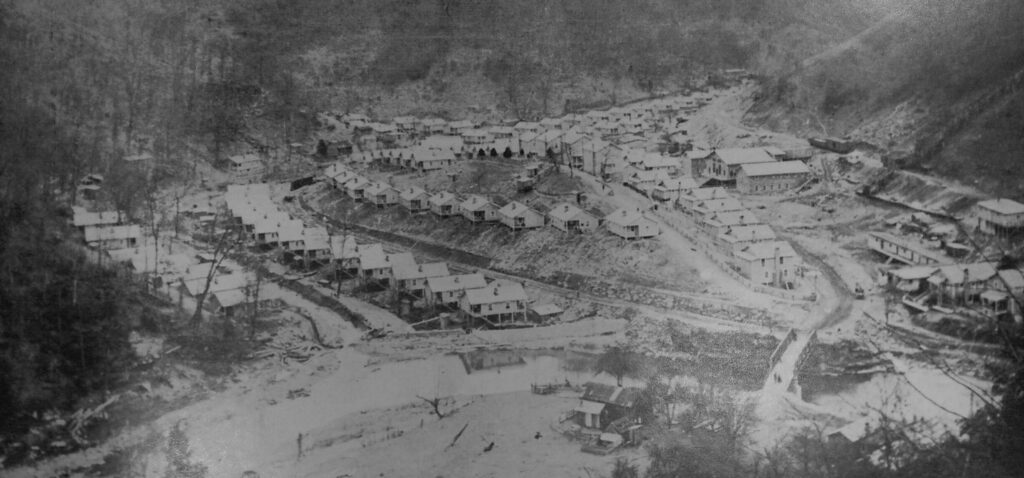

Once mineral and timber rights were obtained, (in some counties upwards of 93% of the mineral rights came to be owned by outside land holding corporations) railroads were laid and coal and timber operations set to work clear cutting the forests and setting up coal mining towns (Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force, 1983; Eller, 1982; Straw & Blethen, 2004).

Our ancestors were quickly swept up into the prevailing socioeconomic culture. Companies like W.M. Ritter began clear cutting the forests that supplied both medicine and food to our people, often subcontracting locals who started their own logging companies.

When the forests were gone, little was left but to scrape what they could from their farms, but even those were becoming smaller as they were split up among children. The soils slowly gave out to over cultivation. As the threat of starvation grew, early mountaineers were left little choice but to work in the coal company towns.3

The Rise of King Coal

Throughout central Appalachia, coal camps and coal company towns were being built that would become infamous for their labor exploitation and human rights abuses. Many companies paid miners in company scrip, thereby making their families completely beholden to the company for their housing and food in company housing and at company stores (Corbin, 1981; Eller, 1982, 2008). Mining was also much more dangerous during those times. Between 1900 and 1950 over 90,000 coal miners died in this nation, not including the thousands more who were permanently disabled in workplace accidents, or those who would die from black lung and silicosis.

For those who still owned land, subsistence agriculture became even more important, providing resilience against mine shut downs stemming from volatile coal markets or to weather lengthy strikes when demanding safer working conditions and better compensation.

During the 30s and 40s, the industry underwent electrification and mechanization which drastically reduced the number of miners needed to mine coal. Unemployment hit record highs and poverty took hold of Appalachian mining communities. Social fabrics frayed as people struggled through abject poverty, furthering the generational traumas that continue plaguing our communities today. Many Appalachians fled north to find work in Ohio (including J.D. Vance’s grandparents) and to the auto manufacturing centers in Michigan. Those who remained in Appalachia struggled through the continued boom and bust cycles of the coal markets.

John F. Kennedy became aware of the region’s growing poverty and sought to address it before he was assassinated. His efforts would later become the War on Poverty launched by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965. It was followed by a media frenzy that showed the worst of the worst of Appalachian poverty.

Inoculated by hillbilly stereotypes that began with the local color writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (painting us as violent, ignorant, buck-toothed, bibbed overall wearing degenerates), the nation looked at us not as victims of a natural resource curse, but as having the “inadequacies of a pathological culture,” as Ron Eller (1982) so eloquently put it (p. xviii). This negative national attention deeply affected our pride and dignity. It also brought in dozens of charity organizations with thousands of privileged people seeking to help, most of whom did not understand the social and political factors affecting our region.

The Appalachian situation improved slightly during the 1970s energy crisis. Demand for domestic energy sent coal prices soaring to phenomenal heights, and by 1975, small coal mines were opening all over Appalachia creating overnight millionaires. Established coal companies built and expanded their larger mining complexes and employed thousands upon thousands of miners with better working conditions thanks to the union. For the first time since the beginning of coal industry, coal miners were earning decent wages with benefits packages comparable to other unionized industries.

Mine safety had also come a long way. When the 1968 Consol #9 mine explosion killed 79 miners in Farmington, WV, it gained national attention through televised national news broadcast. Widows of the mine disaster, assisted by the United Mine Workers, used the public outcry and pressured the federal government into passing the Coal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1969. Though certainly a large improvement, coal politicians kept the newly formed Mine Enforcement and Safety Administration woefully underfunded. Without staff and inspectors to enforce the new safety laws, miners continued dying in preventable accidents. Exactly one year later (to the day) after the 1969 Act was signed into law, an explosion ripped through the Finley mine in Hurricane Creek mine, killing 39 miners.

In 1976 the Scotia mine explosion took the lives of another 26 miners, along with federal inspectors, leading to the passage of the 1977 Mine Safety and Health Act which further strengthened mine safety laws. Despite these advancements, funding and enforcement have always been problematic and underground bituminous coal mining still remains one of the most hazardous occupations in the United States according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the 1990s, coal markets began shifting away from Appalachian coal and sent our region into yet another economic tailspin. Low-sulfur semi-bituminous coal from Montana and Wyoming took over the power generation markets, while foreign steel markets gutted the US steel industry, driving down demand for high grade Appalachian metallurgical coal used in steel production. Along with Reagan era anti-union policies, the Appalachian coal industry used these market fluctuations to close their union mines first and broke the back of the union. Once again, thousands of miners were laid off and poverty began deepening in Appalachia.

When coal markets returned in the late 90s and early 2000s, coal companies increased mechanization through larger surface mines and equipment, giving rise to mountain top removal, a final coup de grace on our mountain communities. Without a union, miners are working longer hours in the mines with fewer benefits.

Today, many companies play the system, mining for a while, then filing bankruptcy to relieve themselves of retirement and healthcare responsibilities, as well as reclamation costs on mine sites they’ve abandoned. Black lung is on the rise with advanced cases showing up in 30 and 40 year old miners. The opioid epidemic that began in our communities thanks to the Sachler Family still tears through the souls of our communities, taking too many lives and ruining so many others. A handful of large coal companies continue their environmental devastation while distant investors reap the rewards. Cancer rates are on the rise along with other poor health outcomes. Our school systems are still grossly underfunded despite hundreds of millions of dollars of coal and natural gas being extracted and exported from our counties each year. Our counties still rank among the top 10% of economically distressed counties in the nation.

And this is why Appalachia is what it is today.

- After Florida, Dry Tortugas and Cape Canaveral: Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. pp. 11–13, 17–18. ↩︎

- During the Civil War, there were many union sympathizers living in the central Appalachian mountains (not just West Virginia). After the Amnesty Act of 1872, former confederates (Democrats) regained political offices in their respective states and at the federal level. It is widely believed that those former confederates punished central Appalachian communities by withholding state revenues for public education and other infrastructure for the public good. Denial of education was also a powerful tool in maintaining a more compliant workforce, hence the anti-literacy laws put in place during chattel slavery in the antebellum south. ↩︎

- Author James Still attempted to capture this difficult transition in River of Earth (1940). ↩︎

References

Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force. (1983). Who owns Appalachia?: Landownership and its impact. The University Press of Kentucky.

Blizzard, W. C. (2010). When miners march. PM Press.

Corbin, D. A. (1981). Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coalfields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922. University of Illinois Press.

Eller, R. D. (1982). Miners, Millhands and Mountaineers: The Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880– 1930. University of Tennessee.

Eller, R. D. (2008). Uneven Ground: Appalachian Since 1945. University Press of Kentucky.

Harris, W. (2015). Truth be told: Perspectives on the great West Virginia mine war : 1890 to the present.

Straw, R. A., & Blethen, H. T. (2004). High Mountains Rising Appalachia in Place and Time.