People ask me “Why do Appalachians vote against their own best interests?” Some are friends who are honestly trying to understand the situation from a point of concern. I know that they seek the cause for the discrepancy, rather than assume coal mining families are incapable of making intelligent political decisions.

The question still stings however, and whether meant or not, it brings up the age old stereotypes of Appalachian people as being backward and ignorant. Most of the time I can separate those who mean well from those who are looking to blame others for the nations current political troubles. The latter tend make another statement, —”Miners are cutting their own throats.”

Such outright condescension pisses me off and explains much of why people back home vote the way they do.1

In his book Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers (1982), Ron D. Eller stated that our nation attributes Appalachia’s social problems to a “pathological culture” rather than the “economic and political realities in the area as they evolved over time.” Nothing has changed. Case in point, J.D. Vance’s bootstraping arguments in his national best seller, Hillbilly Elegy.

The realities Eller speaks of are linked wholesale to the trillions of dollars of natural resources our ancestors inadvertently settled upon 200 years ago, resources that supply our nation’s insatiable desire for all things comfortable and convenient. Suffice to say, this crucial information in the development of Appalachia’s issues has been willfully overlooked in most media representations of our region.

As with most materialism in our country, people don’t want to know about the origins of their lifestyles: the deplorable third world sweatshops filled with children sewing together our latest fashions; the slave labor used to extract precious metals in Africa for our electronics; industrial farming complete with pesticides and antibiotics to maintain productivity; and the exploitation and destruction of Appalachian communities to supply electrical power and steel. When the conscious of American consumers is tinged by occasional news reports about the negative global impact, its easy for many people to engage their cognitive dissonance and dehumanize those affected rather than challenge daily routines in wonderlands of urban convenience.

When it comes to Appalachia, I refuse to let this happen with the people I know and grew up respecting.

I worked with some damn good people in the mines, even some of the foremen. They were hard workers and most had families that loved them, families they’d do anything for. Few people in our nation sacrifice as much to provide for their families as do coal miners. Miners receive special training to work miles underground with the constant danger of roof falls, electrocution, crushing injuries from equipment, suffocation from oxygen deficient air, or explosions—not to mention long term illnesses such as black lung and silicosis. Courage begets pride and some days it takes a lot of courage to take a personnel carrier into the mines when conditions on the section are terrible.

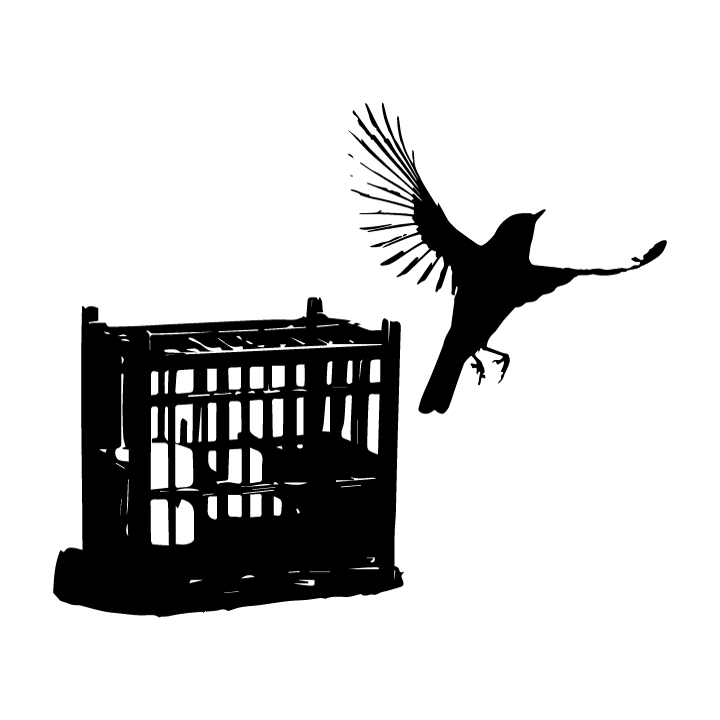

Miners know the risks they face, and many would gladly exchange them for a different job. At the end of the day, coal mining remains the only work in the region capable of feeding, clothing, and sheltering their family with a living wage. It’s the only job that comes with the healthcare benefits necessary to take care of family members fighting cancer, MS, or cystic fibrosis in an area where coal mining has taken a toll on the region’s health outcomes. It’s the only job that can afford their children a ticket out of the “economic and political realities” they are facing.

One coal miner I worked with started in the mines at age 18. At 70 he’d already spent over 50 years working underground. He never failed to show up, and often worked twelve hours a day, six days a week. His work ethic amazed all who knew him and he was given tremendous respect by everyone at the mine. Many of us would ask him why he didn’t retire. He’d humbly say, “It’s all I know how to do, and I enjoy it,” but that was only half of the story. After having sent his own daughters to college, he was now paying to send his granddaughter to James Madison University.

This sense of pride, heritage, and duty to one’s family has been ever present among Appalachia’s coal miners and was the basis of strength for the United Mine Workers. Life in the mountains prior to coal was built upon egalitarian principles and social structures based on how much someone helped their neighbors and friends, not their material possessions. Sure there’s always been a few out there who weren’t “good people,” but they have been the minority.

After busting the unions in the 1990s, coal company associations set to work assimilating our egalitarian values into their public relations and political campaign work. They used it during our safety talks before going underground, making themselves appear as benevolent job providers for our families while attacking environmental regulations that threatened everyone’s economic well being. Rotating shifts and mandatory overtime kept miners in a constant state of fatigue.

What energy we did have during our time off was used up spending time with our families and getting jobs done around the house, not getting involved in civic affairs, or performing the research necessary to refute information we’d been fed. Even if someone did have the time and energy to do the research, speaking out meant putting their family at risk.

It was only through unfortunate circumstances that I myself was able to leave the mines and begin researching the problems in more depth. Sometimes I wish I hadn’t learned so much. I found the work we were doing was causing cancer, not just within ourselves as miners, but our families living in the coalfields, and even people living around coal fired power plants or anywhere else coal is processed and used. When you are working sixty plus hours a week in a dangerous place, it’s much easier to believe that you are helping your family and your nation. It’s much easier to believe that all the bad stuff you hear about the work you do is overinflated half-truths being spun by liberals with an agenda. Letting it sink in that the industry you are working for is hurting other people is simply more than most could bear.

This makes the work of misinforming Appalachians easy for the coal industry and opportunistic politicians. Coal miners are caught in the middle of an information battle between the only decent paycheck in the area, environmental organizations, and politicians who spend more time and money demonizing coal than establishing good paying job alternatives. When men like Michael Bloomberg, who ranks 6th richest person in the nation with an estimated $53 billion in net worth, invest tens of millions of dollars on Sierra Club anti-coal campaigns, but only $3 million in economic development in Appalachia, what are people left to assume about the “War on Coal?”

Then someone asks, “Why are Appalachians voting against their best interests?”

- I realize that when I first started writing this blog, I had similar feelings and spent lots of time trying to work out my love/hate relationship with coal miners. At times, I want to blame them for the willful ignorance they maintain, while other times, I step back to understand the tremendous forces and underfunded school systems that allow for the lack of critical thinking. ↩︎