Growing up on down my hollow, coal trucks were a part of life. They rumbled up and down the road every five to ten minutes starting at 6:00 in the morning and continuing until 6:00 in the evening. From our doublewide perched on the hillside, we could hear them coming, jake breaking into each curve all the way down as far as Jimmy’s truck shop. Paid by the load and not by the hour, drivers careened their 50+ ton tractor-trailers coal up and down our narrow road.

When my brother and I were old enough to take our bikes to the road, Mom made us wait until well after 6 p.m. so we wouldn’t be being caught beneath the 22 wheels of a coal truck. Still we kept our ear to the wind, listening for a truck that got held up, or days when they were running coal later than usual.

Everyone had to have CB radios in their vehicles to avoid being crushed by coal trucks, including our bus driver. The truck drivers named the dangerous curves based on a simple landmarks so they wouldn’t hit each other. All day long, you’d listen to them calling on channel 13 “Volkswagen down,” “Horse Shoe loaded up,” “Meat House loaded,” and “Trailer unloaded.” “Volkswagen” was named for the junked red beetle parked at my grandparent’s house, and Meat House was for the small slaughterhouse my cousin and great uncle ran for people who still raised the occasional beef or hog.

For decades we had dirt roads and the dust covered everyone’s homes. When they finally paved it in the mid 80s and state laws forced truck owners to put tarps over the loads, things got a little better. But on rainy days, their undercarriages would get caked with mine mud, which would fall off as they came back up the hollow. When things dried out, it was pulverized into dust and ended up on our houses, and in our lungs.

My grandmother took to draping old towels over her porch chairs rather than having to wipe them down every time someone came for a visit and wanted to sit on the porch. My uncle purchased a pressure washer to keep his porch floor and vinyl siding clean. And then there was the speed.

Those living nearest the road with little ones petitioned the county to enact a 25 mile an hour speed limit down the road. Truck drivers didn’t like it. They complained and protested having to drop their speed on just three mile stretch of their 20 mile haul. Some even threatened those who’d been most vocal about it, blowing their truck horns every time they passed by their houses.

The county eventually installed a speed limit sign, but the first night it was up, someone cut it down and threw it into the creek below one mother’s yard. But even with the speed limit in place, coal politics saw to it that the speed limit was never enforced.

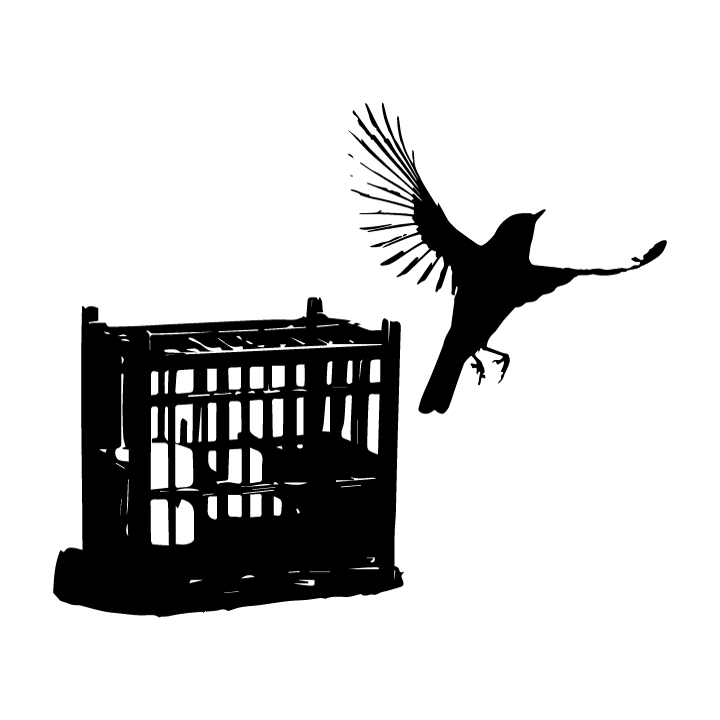

How many tons of coal left our hollow in those trucks? How much money? Load after load, for over 60 years. Now the coal is gone. There hasn’t been a mine down the hollow in over 15 years, and there won’t be another.

The ridges that surrounded us have been torn to shreds. Large holes were punched into the sides that now drain out acidic water and whatever chemicals were left behind. The forests are dissected. Grass and brush are still the only things covering hillsides nearly forty years after the mine sites were reclaimed according to the 1977 Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 that took a literal act of congress to get so coal companies would have to fix the damage they made.

Many of my generation have left the hollow, finding few reasons to stay without good jobs. Many of the once well kept homes and yards are now growing over, junk is piling up, and houses are left abandoned.

Many of the coal operators who made their fortunes down our hollow live well outside of the area. Richard Gilliam is a billionaire and continues to fly in his private jet, living five hours away in Charlottesville, enjoying the beauty of the Shenandoah Valley. The owners of Paramont eventually created Alpha Natural Resources, 3rd largest coal company in the United States following their merger with Massey Energy. They live in Bristol, Virginia miles away from the mountains they laid to waste. Some of the Lamberts’ live in Washington County, Virginia where beautiful farms lay at the base of the Blue Ridge.

Our wells are contaminated and our family springs have turned into mine drainage. No thought has ever been given to the people who would be left with the mess. Our hollow is only one place, one familiar lifelong home among thousands of others left to ruin in the wake of American Progress and the pursuit of personal wealth.

And so is the story of Appalachia, the story of billions—trillions—of dollars of natural resources leaving our mountains, heaved from the Earth by the broken backs and choked lungs of our families. For all of our love of home and our love of family, we have been made dependent upon outside interests—made slaves to others comfort and luxury.