The following is an excerpt from a reflection I wrote December 2015.

It was a warm afternoon when we arrived in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Our Blue Toyota Corolla was overflowing with camping gear, the large Thule setting us apart as travelers, not locals. We’d never been in Mississippi, but as soon as we crossed the border, I felt a sense of uneasiness. Not fear, nor nervousness necessarily, but I was unsettled. The words of Nikki Giovanni’s convocation at Berea College spoke clearly in my mind, “I still fear when my son travels into the south.” I looked back at the kids and knew we were okay. We were white. We would not be racially profiled, pulled over, and harassed—if not worse. I felt sick to my stomach.

Our final destination for the day would be the Chewalla Lake campground where we could stay the night for less than $10, a practice we repeated many times to extend our travel budget for the six-week long trip connecting with organizations regarding the issues of fossil fuel use and extraction. As had become customary, we needed to make a stop for supplies before setting up camp that night. Without any local grocers open in Holly Springs, we headed to the nearby Wal-Mart.

First stop for my son and I was the restroom after being on the road. When it came time to wash our hands, he stood beside me at the adjacent sink and asked solemnly, “Dad, why did someone carve that into the wall?” He pointed towards the words, “I HATE ALL N*****S.” He was 12 at the time. I lowered my head and told him, “Because making things equal by law doesn’t mean it changes some people’s hearts.” I looked up at him and his face was grim. Despite our many discussions about racism, it was his first time seeing it in person.

Americans want to believe that they live in a country built on the principles of freedom, liberty, and justice for all. But no one wants to dredge up the past. They certainly wouldn’t want to think of our country as I now have come to understand it. We look at history of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust with disgust, wondering how any one could have committed such atrocities. Millions of innocent people slaughtered in death camps, in front of firing squads, or used as medical experiments. The only difference between the United States of America and Nazi Germany was time. How many American Indians died by our nation’s hand? How many are still dying because of the conditions they are forced into? How many million Africans were brought here to live out lives of torture and misery to build the nation’s economy? How many Mexicans lost their lives in places like Veracruz during the Mexican-American War because our nation desired more land? If we were able to calculate the number of racially motivated deaths at the hands of our country, directly or indirectly, you would be sick to your stomach. Or should be.

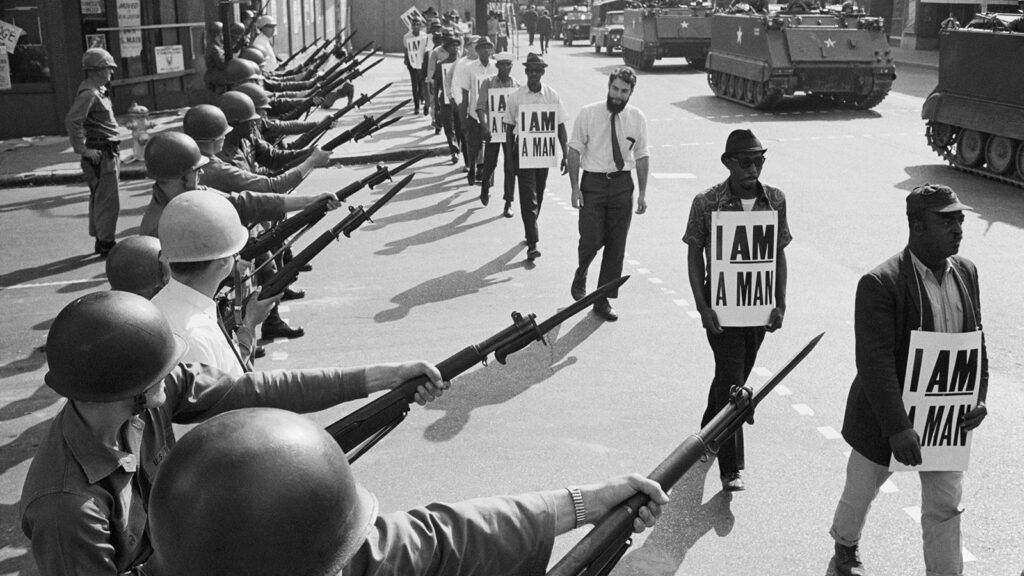

And yet, still today in modern American, people of color born from this terrible history are continually denied justice and equality. They struggle to find hope in a country ruled by money, wreathed in false prominence, and governed by corruption. These minorities fight to dispel the darkness of ignorance and to educate millions of people easily swayed to hatred, easily set to dehumanize and destroy life in the name of economic driven patriotism.

When I look at the efforts of Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, and Marcus Garvey I could not help but wonder how they could keep from falling into deep depression. Educational attainment was even lower during their times, and the horrors of lynching people of color were ever present and acceptable in larger society. Millions of slaves were set free into a country that despised them, did not want them except for their labor in the most unwanted jobs while pushing them to live in the most unwanted places.

Every attempt to rise up was met with destruction: People’s Grocery, Red Summer, and Tulsa being only a few examples. Though violence against African Americans was less prominent in the north, they still faced the institutionalized racism of economic stagnancy, educational and physical starvation, housing inequality, police brutality, and prison sentences.

If history has taught us anything, it is that people can be controlled if they are divided.

There are reasons that people of color all over this world have been systematically oppressed and destroyed. People of color are, or once were, indigenous peoples. They shared a similar nature-centered spirituality and understandings of land and community, finding happiness and freedom through their knowledge of how to live in connection with the natural world they occupied. But these people are a threat to what we deem “modern civilization.”

As stewards of the land, they can teach the rest of us how to live and find happiness without having to subscribe to economic systems that ensure only a select few retain all the power and wealth. In the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau:

The first person who, having enclosed a plot of land, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human race have been spared, had some one pulled up the stakes or filled in the ditch and cried out to his fellow man, “Do not listen to this imposter. You are lost if you forget that the fruits of the earth belong to all, and the earth to no one!”

Even our ancestors in Appalachia knew this. Those who escaped the colonial plantations and their indentured servitude learned from the indigenous peoples who first inhabited the mountains and achieved freedom through land-based subsistence in the mountains. But the new U.S. Government had different ideas for the continent. They actively committed genocide on the Cherokee and other tribes as they broke treaty after treaty, brutally taking their lands before forcing them onto the Trail of Tears.

Our white skin assured us a better fate than the Cherokee. My ancestors fled north from Western North Carolina as soon as Andrew Jackson was elected, ending up resettling in what would become the coalfields. Our claims to the mountains as US citizens were eventually taken through unethical mineral rights purchases. While the Cherokee and other tribes were forced onto more inhospitable lands, our ancestors were economically coerced into forever destroying the mountains and forests along with the remaining cultural knowledge of how to live off of them. Thousands of Appalachians, African Americans, Italians, Yugoslovians, Polish, Germans, and other poor European immigrants would die in the process, some 104,000 miners over the course of a century.

It is the knowledge of continued oppression stemming back generations that drives my desire for equality and justice. This is why the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s work towards the Poor People’s Campaign was so important. This is also why his life was taken as was Malcolm X’s after his return from Mecca. These two men understood that the issues we faced with inequality had a much larger source. They understood that skin color was only a tool used to achieve control. A powerful tool, but only one of many. They understood that the sooner we all realized our shared suffering was based on capitalism, the sooner we could all begin fighting for true justice and equality. The powers who thrive on continued inequality knew this as well.

Everything we are seeking in terms of justice continues to be broken down into us versus them be it left vs. right; black vs. white; citizen vs. immigrant; democracy vs. communism (as maligned in definition as it is); Americans vs. terrorists; Christian vs. Muslim vs. Jew vs. Atheists. We all must realize that there is a powerful force that wants us to fight each other.

Unfortunately, the burden—the greatest and most terrible burden of this fight—will always be borne upon the oppressed. We are the ones who are left to do the work. We are the ones left to find hope where little exists, and to keep fighting and struggling against ignorance and hatred. Not only must we suffer, but we must also continue to find compassion and patience in educating those who intend us harm. We simply cannot accomplish this if we too, hold hatred and malice in our own hearts. We can’t make progress if we continually levy accusations and assume people are jerks and will never change, even among ourselves.

There is a bigger struggle at hand with much greater consequences, and we should understand that each of us has our own part to play in that struggle.